Even in Nephi’s time, despite their leaving Laman, Lemuel and the sons of Ishmael in the land of their First Inheritance where they landed and settled, the crops planted, and whatever improvements they had achieved that first year or so, the Lamanites followed them northward and discovered their settlement area, attacking them on numerous occasions, as Nephi defended his people (Jacob 1:10).

Almost immediately, however, the people “under the reign of the second king, began to grow hard in their hearts and indulged themselves somewhat in wicked practices, such as like unto David of old desiring many wives and concubines, and also Solomon, his son” (Jacob 1:15). By the time of Enos, Jacob’s son, “the people of Nephi did till the land, and raise all manner of grain, and of fruit, and flocks of herds, and flocks of all manner of cattle of every kind, and goats, and wild goats, and also many horses” (Enos 1:21), and there were many wars with the Lamanites (Enos 1:24).

By the time of Jarom, Jacob’s grandson, in 400 B.C., the Nephites had “spread upon the face of the land, and became exceedingly rich in gold, and in silver, and in precious things, and in fine workmanship of wood, in buildings, and in machinery, and also in iron and copper, and brass and steel, making all manner of tools of every kind to till the ground, and weapons of war” (Jarom 1:8).

By this time, the ancient city of Nephi, according to Captain Hernando de Soto in 1533, was protected in a hollow at the northern end of the valley, with an enormous stone fortress, a structure so immense that at first sight de Soto and his companion doubted that any army could breach it. The hills were bare of sward (short grass), no trees except the stunted molle (pepper tree) grew there. The city was laid out in large blocks or squares with straight and narrow, paved streets. It had large plazas, public baths, a house of learning, and factories where the women spun and wove cloth of great beauty. The smaller buildings were painted yellow and red, the larger ones of enormous, beautifully laid stonework.

Like the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, where the setting sun reflected on the cream-colored limestone facade of both ancient and modern structures, which gives them a golden hue, giving rise to the term “Jerusalem of Gold,” which is the unofficial national anthem of Israel and was sung by Israel Defense Forces on Jun 7, 1967, after paratroopers wrested eastern Jerusalem and the Old City from the Jordanians during the Six-Day War (Yaacov Arkin and Amos Ecker, “Report GSI Dec 2007: Geotechnical and Hydrogeological Concerns in Developing the Infrastructure Around Jerusalem,” The Ministry National Infrastructures, Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel, July 2007)—Cuzco’s temple walls had the same effect of reflection, which at one time as the retreating sun’s rays touched the beaten gold plates that adorned its walls the pyramided Sun Temple, towering over the lower buildings around it, gleamed as if it were cast in metal.

By 362 B.C. there had been “wars and contentions and dissensions for the space of much of the time” (Jarom 1:13). By 324 B.C., they had “many seasons of peace, and many seasons of serious war and bloodshed” (Omni 1:3). Sometime after 280 B.C., the prophet Amaleki writes that the Lord commanded Mosiah to depart out of the land into the wilderness (Omni 1:12); and “they departed out of the land into the wilderness, as many as would hearken unto the voice of the Lord; and they were led by many preachings and prophesyings. And they were admonished continually by the word of God; and they were led by the power of his arm, through the wilderness, until they came down into the land which is called the land of Zarahemla” (Omni 1:13).

Evidently, upon leaving the City of Nephi in the area of present day Cuzco, which is located in an Andean valley 11,207 feet above sea level, the Lord led Mosiah through the narrow strip of wilderness, down through the valley and mountain passes to the north and west, between the lakes of Orcococha and Choclococha.

The mountain pass through Huancavelica

heading westward

Then northward through

the valley pass west of Huancavelica and following the Canyon toward Colpa

and turning southwest of there through the Acobambilla District and across to

the Lincha District and dropped down the mountains into the Catahuasi District

and finally out of the mountains and onto the lower plain, then crossed

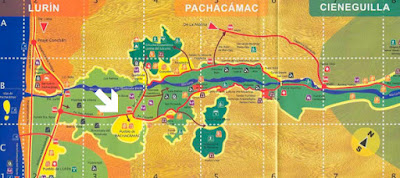

the Lurin valley with relative ease northwest to Pachacamac, an overall

distance of about 620 miles. Another route would have been to head southwest

down through the desert lands to what is present day Nazca, then north to Ica

and along the coast toward Pachacamac, a distance of approximately 700 miles.

East end of the Lurin Valley where the (yellow

arrow) road from the higher Andes drops down through the Pass and along the

rocky ledges

Either way would have

given the Lord plenty of time through his many prophets who delivered “many

preachings and prophesyings” as they were led through the wilderness to humble

the surviving Nephites and mold them into a more righteous people by the time

they reached their destination. “And they

were admonished continually by the word of God; and they were led by the power

of his arm, through the wilderness” (Omni 1:13). By the time these

Nephites, who had “hearken[ed] unto the voice of the Lord” and “depart[ed] out of the land with him, into the wilderness” (Omni 1:12) reached

Zarahemla, they would have been more reliant on the Lord than when they had

been in the City of Nephi.While these two routes are merely speculation, there are hardly any others that a large number of people could have traversed from Cuzco to Pachacamac in the days before roads. Passes through and down out of the mountains are limited and the drop in terrain from over 11,000 feet down to 2,000 feet along the foothills and eventually 250-feet at Pachacamac.

Meanwhile, some centuries earlier, a small band of people made up of palace guards, servants and royal retinue wound their way secretively out of Jerusalem, carrying with them a young prince, probably little more than a baby, who they affectionately referred to by the endearing term “Mulek,” or “Little King.” They escaped the Babylonian hordes laying siege to Jerusalem and traveled south toward the Red Sea, then southeast along its coast as “they journeyed in the wilderness, and were brought by the hand of the Lord across the great waters, into the land where Mosiah discovered them; and they had dwelt there from that time forth” (Omni 1:16).

The narrow Lurin Valley stretching from the

Pacific Ocean inland to the east. (White Arrow) Pachacamac is about ½-mile

inland from the coast

The

land where Mosiah discovered them, of course, was the land of Zarahemla. As

Amelaki stated it: “and they were led by the power of

his arm, through the wilderness, until they came down into the land which is

called the land of Zarahemla. And they discovered a people, who were called the

people of Zarahemla. Now, there was great rejoicing among the people of

Zarahemla; and also Zarahemla did rejoice exceedingly” (Omni 1:13-14).Anciently, people almost always settled along the coast when first landing, not moving inland for many generations, and then usually up large rivers because of the fresh water source they provided. It would have been extremely unusual for the Mulekites to come into the land called Zarahemla and move inland any distance at all away from the coast. In fact, in this area, the Mulekites would have had direct access to three large fresh-water rivers flowing down out of the mountains and into the sea—the Chillon, Rimac and Lurin rivers.

To us today, it doesn’t matter much, because there are developed resources almost everywhere—but around 600 B.C., as the first to come into that land, the Mulekites would have remained along the coast and settled there, where rivers flowed out of the mountains, down into the foothills, and to the coast. And this is where Mosiah eventually found them in their land they called Zarahemla.

(See the next post, “Pachacamac: The City of Zarahemla – Part II,” for more information on where the Mulekites settled and Mosiah found them along the cost near Lima, Peru)

No comments:

Post a Comment